Ed Ruscha

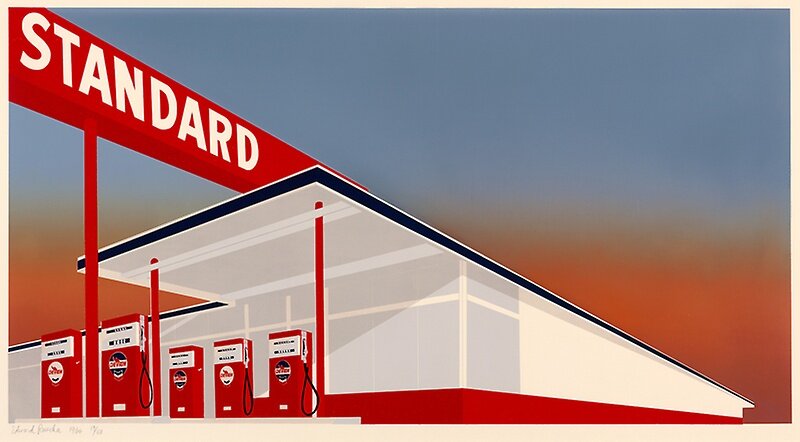

For those who don’t know him, Ed Ruscha is an artist who grew up in Omaha and Oklahoma City, and then migrated to southern California, where he became a leading member of the Pop Art movement that brought us the likes of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claus Oldenburg, among many others. His best known painting is of a Standard Oil Station in Amarillo, Texas, which reflects a blend of Art Deco and abstraction, reducing the station architecture to its basic geometrical elements.

Ruscha works in a number of visual media, including photography, painting, film, and collage. He likes to incorporate text into his works.

I find his photographic works to be inspirational, including his photo books, which include TwentySix Gasoline Stations and Hollywood Boulevard. For the latter, Ruscha used a motorized camera to photograph every building along Hollywood Boulevard in a flat style. Ruscha traffics in banality, using utilitarian objects and buildings as subject matter. I own a Steidl reissue of the Hollywood Boulevard book.

Given my longstanding interest in Ruscha’s work, I was not going to miss his 11:00 AM talk at the Art Institute of Chicago today. It was sponsored by the Institute’s Woman’s Board—in 2019, why do some cultural institutions still have woman’s [sic] board?

No one could have mistaken Ruscha for an artist when he walked on stage dressed in a plaid shirt, dark slacks, and a formless black jacket. He is thin, and walks with a slight limp (left leg). No paint stains, wild beard, or crazed look in his eyes. His outward character could easily be that of his father, who was an auditor for the Hartford Insurance Company. It also summarizes his plain-spoken manner, as well as the content of his talk.

Like almost every modern speaker, Ruscha relied on a PowerPoint presentation, but in Ruscha’s there was no text independent of the artworks that Ruscha chose to illustrate his talk. He basically used each image to riff about his art, creative process, and life As is the case with most artists, Ruscha didn’t offer the magic key to unlock the meaning of his lifelong output. In fact, the biggest clue came when he projected Japser John’s Flag on the screen. He first noted that he was intrigued by John’s name. How could he not find John’s work interesting with a name like that? Second, and probably more revealing, he liked the fact that John’s said (paraphrased), “People focus too much on the flag” when they look at the painting.

There were other clues, however. The first image he displayed was Monarch of the Glen by English landscape painter, Sir Edwin Landseer. It had sentimental value to Ruscha because it served as the basis for the Hartford Insurance Company’s elk logo, which Ruscha remembered from his youth. There you have a key or the genealogy behind Ruscha’s work: A formal landscape painting that was simplified so that it could serve as a corporate logo. It is not a coincidence that Ruscha worked as a layout artist in an L.A. advertising agency and Artforum magazine.

In terms of older works, Ruscha also projected John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1852), which hangs in the Tate Britain. I recognized it as the painting that was used on the cover of a Pearls Before Swine album entitled Beautiful Lies You Could Live In. Ruscha seemed to be intrigued by two facts: First, the female figure was painted using a model in a bathtub. Second, nobody knew where the marsh or riverbank was located until a horticulturist examined all the plants and trees depicted in the paintings, permitting him to pinpoint the location.

Ruscha also projected one of his famous word paintings with mountains serving as the backdrop. He said mountains were the perfect background, and then he noted the name, dates, and short phrase plastered across the mountains were what he imagined might appear on a fictional tombstone. Many of his word works bring Jenny Holzer’s to mind works—Holzer’s works are often projected on buildings or displayed on LED signboards.

Ruscha also commented on the type font. It had no curves; just lines. He referenced the Boy Scouts when giving it a name.

Ruscha also displayed a painting that he made in 2017 of the American flag in tatters against a dark background. The woman who was seated on stage with Ruscha asked whether the painting reflected Ruscha’s views about the state of the country. I don’t recall his exact words, but they came out evasively as his face dryly smiled. The subtext: “You shouldn’t have to ask that question.” It was obvious, but of more significance, the painting pays homage to Jasper Johns, one of Ruscha’s early influences.

Toward the end of the 50-minute talk, Ruscha chose to display images of U.S. currency. He was deeply offended with the Bureau of Engraving’s decision to modernize the figureheads on bills. For Ruscha, the original images were better than the updated ones, which were intended to make the figures look younger and more like people from our times—smoother skin, less hair on the face. For Ruscha, there was no need to do this.

After his talk, the audience was given the opportunity to ask questions. It was not a curious audience, which is no surprise. The front section of the hall was reserved for Tom Wolf’s social X-rays, who had been escorted to their assigned seats by subtly obsequious staff members who hoped their feigned interest in each person would eventually produce more money for the Art Institute. I wanted to ask Ruscha what it was like to appear before an audience of wealthy patrons who would not have given him the time of day before his paintings sold in the seven-figure range, but I thought it best to keep my thoughts to myself.

Probably the best insight into Ruscha and artists in general came when Ruscha was asked what he did when he didn’t want to go to his studio. He responded that he is happiest when he is in the studio, which, like other artists, is filled with his favorite objects. He loves the creative process.

Monarch of the Glen by Sir Edwin Landseer (1851)

Standard Oil Station, 1966 by Ed Ruscha

Ophelia by John Everett Millais

Fold out from Hollywood Boulevard by Ed Ruscha

From TwentySix Gasoline Stations by Ed Ruscha

OUR FLAG, 2017, by Ed Ruscha